Book review

The Tree of Knowledge

The Biological Roots of Human Understanding

Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela (1992)

This is one of several reviews I published at Goodreads – though “review” is too charitable; rather they’re brief notes on what caught my attention reading the book, or things I ought to remember in the future about it. Enjoy, maybe?

This is the best book I’ve read probably since I began to read. Undoubtedly, it is at least the conceptual cherry in the proverbial intellectual cake I’ve been cooking for at least the past two years as I reflected upon and studied about justice, political philosophy, sociology, anthropology, psychology, as well as, most notably recently, systems theory, complexity and cognitive science.

Through existing we “put forth a world” that is a result not of direct contact with “objective external reality” (thus not a representational mind) nor a fantasy of our imagination (thus not a solipsistic dreamland). We experience reality as autonomous unities in “structural coupling” with the environment which, for each of us, include other beings as well.

The main takeaway of this view, for myself, lies in short in its ability to present incredible insights into human cognition and behavior while making it clear how they are absolutely incompatible with traditional notions of ‘objectivity vs. subjectivity’, free will/agency, ‘nature vs. nurture’, certainty, reason, and education. To accept it as credible (and the core of this theory is all but incredible – indeed, once one “creeds” it, it is impossible to dispel one’s mind of it without being aware one is refusing to think – and that is ‘knowing how we know’); to accept it as credible is to necessarily accept a most drastic notion of equality: one’s view of the world is unique, a result of one’s own social/nurtural (ontogenic) history and one’s biological/natural (philogenic) history. That means we are equal in our uniqueness of limitation. The world we perceive and think about cannot be any other than the one we put forth through our own cognition. Thus, the world a 21st century American woman perceives and lives in, though ‘objectively’ the same, is filled with values, notions (or lack thereof) of right, wrong, old, new, roles, goals, that are for the most part wildly different than the ones through which, say, a native Mongolian in the 15th century perceived.

It is not just that we are different because we learned different things. Our brains quite literally are unable to perceive (or rather, should I say ‘produce’?) the same meanings in reality. We are who we are born, but also (and _that_ is why we disagree so much everywhere) who we become as we live – one is indissociable from another. Autonomy/freedom is only perceived as a phenomenon through our social coupling, and such social coupling only comes about through our biological/embodied reality, from whence we can never escape, for it is who we are, and to escape it would mean to be something else.

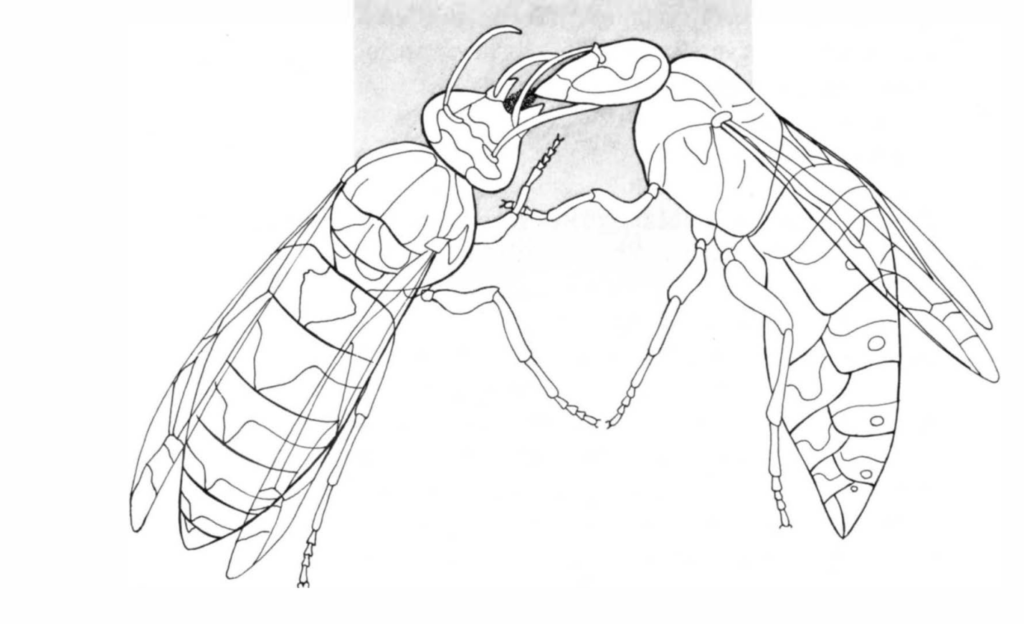

“Mechanism of coupling between social insects: trophallaxis”, figure from p. 187. Cells, as well as insects and higher vertebrates, all have mechanisms for coupling their structures and “communicating”.

I could spend hours talking about it, but that might be mostly pointless – it is usually easier for one to read the book itself, and besides what I took away from it is not a result of the book by itself and my ‘interpretation’ of it, but rather -in fashion with the book itself- of my past experiences, that have helped shape my awareness of such ideas.

So please, do read this.

It is highly accessible, requires no prior understanding of its subjects (beyond basic high school biology), and will enable you, if you give yourself into it, to become someone new – or, rather, to be more aware of what you are, and what you are not.

The following passage from the last chapter of the book helps illustrate my amazement a little, and will close this review:

“The knowledge of knowledge compels. It compels us to adopt an attitude of permanent vigilance against the temptation of certainty. It compels us to realize that the world everyone sees is not *the* world but *a* world which we bring forth with others. It compels us to see that the world will be different only if we live differently. It compels us because, when we know that we know, we cannot deny (to ourselves or to others) that we know.

That is why everything we said in this book, through our knowledge of our knowledge, implies an ethics that we cannot evade, an ethics that has its reference point in the awareness of the biological and social structure of human beings, an ethics that springs from human reflection and puts human reflection right at the core as a constitutive social phenomenon. If we know that our world is necessarily the world we bring forth with others, every time we are in conflict with another human being *with whom we want to remain in coexistence*, we cannot affirm what for us is certain (an absolute truth) because that woudl negate the other person. If we want to coexist with the other person, we must see that *his certainty – however undesirable it may seem to us – is as legitimate and valid as our own* because, like our own, that certainty expresses his conservation of structural coupling in a domain of existence – however undesirable it may seem to us. Hence, the only possibility for coexistence is to opt for a broader perspective, a domain of existence in which both parties fit in the bringing forth of a common world. A conflict is always a mutual negation. It can never be solved in the domain where it takes place if the disputants are ‘certain.’ A conflict can go away only if we move to another domain where coexistence takes place. The knowledge of this knowledge constitutes the social imperative for a human-centered ethics.”